Never Forget: Is our world a better place than ever before?

Moderator: Moderators

Now I'm just trying to understand. My wife made a statement along the lines that if someone's hurting in South Sudan or another land locked country full of bullshit strife, it's far easier to get out and seek refuge. Does that alone make it a better world for someone living in conditions like that? I was a 3rd worlder* who became a first worlder when I moved. I'm in better circumstances than most of the country. But I'm not at all familiar with a situation as described in this post.

**As a first worlder, I live in a rich state that has damn good amenities and I I'm very near the upper edge of middle class going towards upper middle class. Even in India, which isn't even close to being a bad 3rd world nation, I was upper middle class. My family owned a home, sent two kids to two different private school and me to an exclusive school run by India's scientific community. Most of India goes to private instead of public since public sucks. I lived in a metropolis. So while I have some inkling of what poverty can be, I've suffered it only for a few years when we moved to America and earlier for a few years when I was really young. Too young to remember mostly. I don't know what third world behavior or aid to these countries actually is.

Is it easier for a Sudanese or any other war-torn African to escape and get asylum? I've totally been proved I was wrong about everything else I said in this thread and my wife has laughed at me in my face brandishing her rightness. But, this is one of those things I don't know enough about and I want more info before I can agree or refute her.

**As a first worlder, I live in a rich state that has damn good amenities and I I'm very near the upper edge of middle class going towards upper middle class. Even in India, which isn't even close to being a bad 3rd world nation, I was upper middle class. My family owned a home, sent two kids to two different private school and me to an exclusive school run by India's scientific community. Most of India goes to private instead of public since public sucks. I lived in a metropolis. So while I have some inkling of what poverty can be, I've suffered it only for a few years when we moved to America and earlier for a few years when I was really young. Too young to remember mostly. I don't know what third world behavior or aid to these countries actually is.

Is it easier for a Sudanese or any other war-torn African to escape and get asylum? I've totally been proved I was wrong about everything else I said in this thread and my wife has laughed at me in my face brandishing her rightness. But, this is one of those things I don't know enough about and I want more info before I can agree or refute her.

Ancient History wrote:We were working on Street Magic, and Frank asked me if a houngan had run over my dog.

I'm sorry, I'm confused. You seem to think India is a '3rd world nation'.

What are your definitions for that then?

Because it makes you sound like a crazy person afaik.

What are your definitions for that then?

Because it makes you sound like a crazy person afaik.

Gary Gygax wrote:The player’s path to role-playing mastery begins with a thorough understanding of the rules of the game

Bigode wrote:I wouldn't normally make that blanket of a suggestion, but you seem to deserve it: scroll through the entire forum, read anything that looks interesting in term of design experience, then come back.

Hmmm my bad then, read it as India being a (not bad) 3rd world nation

Gary Gygax wrote:The player’s path to role-playing mastery begins with a thorough understanding of the rules of the game

Bigode wrote:I wouldn't normally make that blanket of a suggestion, but you seem to deserve it: scroll through the entire forum, read anything that looks interesting in term of design experience, then come back.

That was my reading as well. Since Cynic identifies as a former 3rd worlder (hailing from India) and says that India isn't a bad 3rd world nation.ishy wrote:Hmmm my bad then, read it as India being a (not bad) 3rd world nation

Your and my interpretation seems not just reasonable, but expected.

Cynic may have meant that India was a 3rd world nation but is not one any longer.

But the implication is strong that India = 3rd world and I presume he meant 3rd world as developing country, which it totally is, rather than the original usage of 3rd world to describe its stance in the capitalism vs. communism alliances (3rd world being those who allied with neither during the cold war), which India also qualifies as.

Ahh, that's probably my idiocy in not checking over my post before hitting the submit button.

I was trying to imply (failing horribly) the status usually given as a developing country that India usually falls under but I'm not really sure if this is actually true anymore. But looking at the situation, I can tell that it India still falls under the rule. Rationed food, No constant source of clean water and electricity, etc.. But yes, in the old definition India was definitely part of the capitalism V communism alliance. Weirdly. It had strong economic and scientific ties with the Soviet Union while expressing its own ideas of being an independent democracy.

It was hopped up on my meds when i made the post so I meant to imply that India was a 3rd world country but in a much better place than most other 3rd world countries.

I was trying to imply (failing horribly) the status usually given as a developing country that India usually falls under but I'm not really sure if this is actually true anymore. But looking at the situation, I can tell that it India still falls under the rule. Rationed food, No constant source of clean water and electricity, etc.. But yes, in the old definition India was definitely part of the capitalism V communism alliance. Weirdly. It had strong economic and scientific ties with the Soviet Union while expressing its own ideas of being an independent democracy.

It was hopped up on my meds when i made the post so I meant to imply that India was a 3rd world country but in a much better place than most other 3rd world countries.

Ancient History wrote:We were working on Street Magic, and Frank asked me if a houngan had run over my dog.

Of the three articles I linked, the first was US medical achievements, and the second was general scientific advances. I can see how neither of those would seem directly applicable to super poor people in war-torn failed states. Understandable. But the third article did point out a major change that has happened even for the poorest africans: they have cell phones. That is a big deal. A really big deal. Phones are not just for communication between distant family members, or in emergencies. They let you look broadly for work, get internet access (check crop prices, get legal help, etc), minimize travel costs, develop your own business.

Cell phones also give people access to banking, to emergency public health alerts, to election monitoring, and more. It's easy to overstate the value of cell phones (they won't stop a bunch of armed thugs from raping you and murdering your family), but they bring a huge, and mostly unanticipated, change in the lives of many of the poorest people in countries like South Sudan or Bangladesh.

Cell phones also give people access to banking, to emergency public health alerts, to election monitoring, and more. It's easy to overstate the value of cell phones (they won't stop a bunch of armed thugs from raping you and murdering your family), but they bring a huge, and mostly unanticipated, change in the lives of many of the poorest people in countries like South Sudan or Bangladesh.

-

Username17

- Serious Badass

- Posts: 29894

- Joined: Fri Mar 07, 2008 7:54 pm

If your question is whether it is easier for people to escape war torn disease ridden shit holes with bad water and no healthcare now than it was in the past... the answer is obviously "Yes". Some non-zero number of people do in fact escape from places like Somalia to live in Sweden or something these days. And three hundred years ago, none of them did because everywhere they could go was also a war torn disease ridden shit hole with bad water and no healthcare.

-Username17

-Username17

-

Frank Shannon

- NPC

- Posts: 9

- Joined: Tue Nov 22, 2011 2:46 am

- Contact:

The Archdruid Report

Recently I started reading the archdruid report, which argues that as fossil fuels run out over the next century or so the Industrial age will come to an end and people will have to accept a much lower standard of living than what prevails today.

I think he is right, but I really hope he is wrong. If anyone here can debunk his argument I'd really appreciate it.

Thanks

I think he is right, but I really hope he is wrong. If anyone here can debunk his argument I'd really appreciate it.

Thanks

Nah.

Fossil fuels will get much more expensive and unworkable as supplies get more expensive to extract, but we really can move to ethanol or biodiesel or alcohol or any number of other options for a portable fuel source to run things. It's really just a matter of cost.

The only reason we don't do it now is that it's expensive to switch over and the fact that billions of gallons of oil literally spew out of the ground for free if you drill a well.

Hell, if solar energy continues to gain in efficiency and continues to get cheaper, we may just make gas from agricultural waste. You can actually make synthetic oil for $150 a barrel at current energy prices, so cutting those prices with cheap solar could make it a viable option.

The only thing that's decreasing standard of living is the death of middle class. Blame the political power of the plutocrats for that.

Fossil fuels will get much more expensive and unworkable as supplies get more expensive to extract, but we really can move to ethanol or biodiesel or alcohol or any number of other options for a portable fuel source to run things. It's really just a matter of cost.

The only reason we don't do it now is that it's expensive to switch over and the fact that billions of gallons of oil literally spew out of the ground for free if you drill a well.

Hell, if solar energy continues to gain in efficiency and continues to get cheaper, we may just make gas from agricultural waste. You can actually make synthetic oil for $150 a barrel at current energy prices, so cutting those prices with cheap solar could make it a viable option.

The only thing that's decreasing standard of living is the death of middle class. Blame the political power of the plutocrats for that.

-

Frank Shannon

- NPC

- Posts: 9

- Joined: Tue Nov 22, 2011 2:46 am

- Contact:

I think that "just a matter of cost" is a bigger matter than you might think. I think that we just cant get enough ethanol or biodiesel to maintain our current civilization. What really convinced me was the fact that solar which was supposed to be almost viable as an alternative with oil at 25$ a barrel seems to still be "almost" viable with oil now permanently at 100$ a barrel.

But I really cant to justice to his argument so I'm going to reprint one of his old columns without permission. Hopefully he won't mind. I think this give a fair sample of his thinking. Unfortunately it is long but I hope some of you read it anyway. Thanks.

Wednesday, August 26, 2009

Entropy Gets No Respect

The relation between modern industrial society and the scientific ideas that supposedly guide it is more complex than a casual glance will necessarily reveal. The ideology a society believes that it embraces and the assumptions about the world that actually underlie its actions and institutions are not uncommonly at odds with one another. It often takes the most strenuous sort of willed inattention to fail to notice the gap, but efforts toward that end can count on the support of public opinion as well as the more tangible backing provided by economic interests.

Consider the clash between the Christian and liberal values allegedly embraced by the great powers of 19th century Europe and the ruthless political and economic exploitation imposed by these same powers on the subject peoples of their huge colonial empires. The result was a rush to find some justification for European empires other than the obvious one, which was simply that Europeans wanted the wealth and power they could get by exploiting the rest of the planet. As Stephen Jay Gould chronicled in his engaging The Mismeasure of Man, generations of scientists thus spent their careers trying to argue that the “white race,” that imaginary and variously defined beast, was biologically superior to the other “races” on the planet.

These efforts fell afoul of a minor detail of anthropology. It so happens that people of European descent fall toward the middle range of a great many biological indices; people of African descent tend toward one end of most of these indices, and people of East Asian descent tend toward the other. Thus it proved impossible to argue, say, that Britons were superior to Africans without providing evidence that Chinese were superior to Britons, and claims that Britons were superior to Chinese ended up just as effectively proving that Africans were superior to Britons. Still, these efforts continued right up into the first half of the 20th century, because the alternative was to admit that European domination of the planet was a straightforward act of piracy backed by nothing more edifying than a temporary advantage in military technology.

The industrial nations of the early 21st century are in a very similar predicament – or, more precisely, in two very similar predicaments. On the one hand, the relationship between the industrial nations and their Third World client states is very little more equitable than that between the British, say, and the quarter or so of the Earth’s land surface that was occupied by British troops and exploited by British economic interests in the 19th century. Claims of racial superiority having fallen out of fashion, the industrial nations nowadays justify their position by claiming that their political and economic institutions are superior, and the rest of the world’s nations can share exactly the same lifestyles of abundance if they only adopt these.

Today’s industrial societies treat this claim as a self-evident truth. Of course the colonial powers of the 19th century treated the claim of European racial superiority as a self-evident truth, too, and the two claims are equally bogus. The abundance enjoyed by the world’s industrial nations just now, after all, is the result of the fact that those same industrial nations use the great majority of the world’s fossil fuel production. Given that the current industrial nations have burnt around half the planet’s fossil fuel resources themselves, leaving the remaining half to fuel themselves and the rest of the world in the future, dangling the carrot of industrial prosperity in the faces of Third World countries at this point in the historical process is dishonest at best.

Of course it does seem to be true that representative governments and corporate-capitalist economies are more efficient than the competition at turning abundant fossil fuels into suburban lifestyles. This does not make representative governments and corporate-capitalist economies the cause of the prosperity of today’s industrial nations, any more than the skin color of people from Europe was the cause of Europe’s ascendancy during its age of empire. Still, just as the unmentionable realities behind European imperialism made it inevitable that there would be attempts to justify it via bad science, the equally awkward realities behind the ascendancy of today’s industrial powers provide the push behind well-meaning attempts to package the industrial world’s institutions for export to the Third World.

The same sort of logic, on an even deeper level, governs the relationship between the nations of the modern industrial world and the foundation of those nations’ present prosperity – the Earth’s fossil fuel reserves themselves. The hard reality is that the minority of us who happened to have been born in a few powerful countries squandered half a billion years of stored photosynthesis to give ourselves a brief period of spectacular economic abundance, and by doing so, foreclosed the chance that anybody else would enjoy that same abundance in the future. Fossil fuels are not renewable resources in any time frame accessible to our species. Every barrel and ton and cubic foot of fossil fuel we use now is subtracted from the total available to our descendants; despite an orgy of handwaving, no other resource can provide anything approaching the glut of cheap abundant energy on which our lifestyles of relative privilege depend.

Yet this point of view is at least as unmentionable in polite society just now as were the gritty realities of European colonialism in its time, or the equally gritty facts underlying the ascendancy of the world’s industrial nations over the Third World today. The strenuous efforts to find a racial basis for European supremacy a century ago, and the equally vigorous efforts to hold up contemporary Western institutions as the key to prosperity and peace in the Third World today, thus have precise equivalents in the enthusiasm with which every imaginable alternative energy resource gets treated by government officials and media pundits throughout the industrial world.

None of these resources can actually provide the cheap abundant energy needed to maintain the kind of society we have today. I know that this is a controversial statement just now. Still, it’s worth noting that every alternative energy resource that’s actually been brought into production has turned out, at best, to provide a modest increment to existing energy supplies, and that only if you don’t keep track of the energy subsidy the new resource gets from fossil fuels. Of course technologies that haven’t been put into production look more promising, and the further they are from implementation, the more impressive they look; hype, often geared to the very practical goal of selling shares in IPOs, is at least as abundant in the energy field as anywhere else.

And this, dear reader, is where the gap between our society’s official respect for science and its real attitudes toward the world shows up with remarkable clarity.

Once again, the role of the B-movie heavy in this drama is played by the second law of thermodynamics, better known as the law of entropy. As mentioned in a previous post, this is the gold standard of physics, the law you can’t break without, as Sir Arthur Eddington put it, collapsing in deepest humiliation. Everybody in the industrial world with the least smattering of a scientific education knows about it, or at least was introduced to it, and yet next to nobody wants to talk about how it affects the emerging energy crisis of our time.

The crucial implication of the law of entropy, for our purposes, is that it’s not energy as such, but a difference in energy potential, that allows work to be done. Imagine two smooth round boulders of equal weight, one of them sitting on a flat plateau and the other sitting on the slope of a steep hill. If the two are at the same distance from the center of the Earth, gravitation gives them exactly the same amount of potential energy. Still, if you give the one on the plateau a push, you aren’t likely to do anything but strain your muscles, while if you give an equal push to the one on the slope, you may send it rolling down the hill, squashing everything in its path.

The difference is that every part of the plateau has the same energy potential due to gravity, while every part of the slope does not have the same potential, and the boulder rolling down the slope can cash in some of the difference in potential to keep itself moving. The greater the difference in potential, the greater the payoff in terms of energy released. Notice, though, what happens when the boulder on the slope finally lurches to a stop at the bottom of the valley below: it stops, and another push won’t get it going again. It still has a lot of potential energy in that position – it has, in theory, 4500 miles to fall until it reaches the center of the earth – but there’s nowhere it can go to release any of that energy. Without a difference in potential, how much energy you’ve got is a meaningless statistic. (This is, incidentally, why the quest for zero point energy is an exercise in absurdity; by definition, zero point energy is at the lowest possible potential state, and therefore cannot be made to do any work at all.)

The same rule applies to every energy resource: there has to be a difference in potential that allows energy to be released, and the bigger the difference, the bigger the benefit. With petroleum, the difference is in chemical energy. Those long chains of carbon and hydrogen atoms have a lot of energy to release when they come apart and combine with highly reactive oxygen instead; the short chains that form natural gas have less, and the carbon in coal has less still, though it’s still a lot by the standards of other energy sources. All the extraordinary things our species has done with fossil fuels over the last three hundred years are functions, in effect, of the difference in chemical potential energy between a barrel of oil and a cloud of smoke.

Why are these reflections as welcome in the collective conversation of our time as a slug in a fresh green salad? Because they point up the profoundly shortsighted nature of the decisions that made the world in which all of us now live. The immense potential energy locked up in fossil fuels was put there by millions of years of photosynthesis. It’s as though, to return to our metaphor, living things down through the ages rolled boulders uphill and perched them high above the valley floor. After a half billion years or so, our species came along, and figured out how to roll those boulders downhill. As long as there are still plenty of boulders in place, we can continue using them, but when the rate at which we want to send boulders rolling downhill outstrips the boulder supply, it’s a waste of breath to insist that we can get the same results by bouncing pebbles across the valley floor.

This is basically what the more enthusiastic proponents of alternative energy are saying. By the time sunlight gets to us, after traversing 93 million miles of empty space, it’s simply not that concentrated an energy source; that’s why it took the Earth’s photosynthetic organisms so many millions of years to build up the energy reserves we now squander so freely. Wind and hydroelectric power are both secondhand sunlight, the product of natural cycles driven by the sun; the same is true of every kind of biofuel, of course. Nuclear energy is the one nonsolar energy resource we’ve got, but it has severe problems and limitations of its own, not least the fact that the fossil fuel inputs needed to build, run, and decommission a nuclear reactor are so vast that there’s a real question whether nuclear power is a net energy source at all. (Of course the further a nuclear technology is from actual implementation, the better it looks, and the ones that are still vaporware look best of all.)

Does this mean alternative energy is a waste of time? Of course not. Modest as the energy outputs from alternative sources are, they’re what we’ll have to work with when the fossil fuel is gone. What it means, rather, is that the particular kind of civilization we’ve built in the last three centuries will not survive the end of cheap abundant fossil fuels. A society that is used to getting things done by rolling huge boulders down steep slopes is going to have to learn to make do on the much less lavish results of bouncing pebbles across the flat.

The problem here is that very few people want to deal with that reality. The great majority will make themselves believe in zero point energy and evil space lizards and any other absurdity you care to name, rather than gulp and take a deep breath and admit that the prosperity we’ve enjoyed for the last three centuries was bought at our grandchildren’s expense. I sometimes suspect that one of the reasons so many people like to imagine an apocalyptic end to the industrial age is that sudden extinction is easier to contemplate than the experience of slowly waking up to the full extent of our own collective stupidity.

And that, dear reader, is why entropy has become the Rodney Dangerfield of the contemporary energy debate. It may be the gold standard of physics, but in the collective conversation about our future, it don’t get no respect.

******************l

But I really cant to justice to his argument so I'm going to reprint one of his old columns without permission. Hopefully he won't mind. I think this give a fair sample of his thinking. Unfortunately it is long but I hope some of you read it anyway. Thanks.

Wednesday, August 26, 2009

Entropy Gets No Respect

The relation between modern industrial society and the scientific ideas that supposedly guide it is more complex than a casual glance will necessarily reveal. The ideology a society believes that it embraces and the assumptions about the world that actually underlie its actions and institutions are not uncommonly at odds with one another. It often takes the most strenuous sort of willed inattention to fail to notice the gap, but efforts toward that end can count on the support of public opinion as well as the more tangible backing provided by economic interests.

Consider the clash between the Christian and liberal values allegedly embraced by the great powers of 19th century Europe and the ruthless political and economic exploitation imposed by these same powers on the subject peoples of their huge colonial empires. The result was a rush to find some justification for European empires other than the obvious one, which was simply that Europeans wanted the wealth and power they could get by exploiting the rest of the planet. As Stephen Jay Gould chronicled in his engaging The Mismeasure of Man, generations of scientists thus spent their careers trying to argue that the “white race,” that imaginary and variously defined beast, was biologically superior to the other “races” on the planet.

These efforts fell afoul of a minor detail of anthropology. It so happens that people of European descent fall toward the middle range of a great many biological indices; people of African descent tend toward one end of most of these indices, and people of East Asian descent tend toward the other. Thus it proved impossible to argue, say, that Britons were superior to Africans without providing evidence that Chinese were superior to Britons, and claims that Britons were superior to Chinese ended up just as effectively proving that Africans were superior to Britons. Still, these efforts continued right up into the first half of the 20th century, because the alternative was to admit that European domination of the planet was a straightforward act of piracy backed by nothing more edifying than a temporary advantage in military technology.

The industrial nations of the early 21st century are in a very similar predicament – or, more precisely, in two very similar predicaments. On the one hand, the relationship between the industrial nations and their Third World client states is very little more equitable than that between the British, say, and the quarter or so of the Earth’s land surface that was occupied by British troops and exploited by British economic interests in the 19th century. Claims of racial superiority having fallen out of fashion, the industrial nations nowadays justify their position by claiming that their political and economic institutions are superior, and the rest of the world’s nations can share exactly the same lifestyles of abundance if they only adopt these.

Today’s industrial societies treat this claim as a self-evident truth. Of course the colonial powers of the 19th century treated the claim of European racial superiority as a self-evident truth, too, and the two claims are equally bogus. The abundance enjoyed by the world’s industrial nations just now, after all, is the result of the fact that those same industrial nations use the great majority of the world’s fossil fuel production. Given that the current industrial nations have burnt around half the planet’s fossil fuel resources themselves, leaving the remaining half to fuel themselves and the rest of the world in the future, dangling the carrot of industrial prosperity in the faces of Third World countries at this point in the historical process is dishonest at best.

Of course it does seem to be true that representative governments and corporate-capitalist economies are more efficient than the competition at turning abundant fossil fuels into suburban lifestyles. This does not make representative governments and corporate-capitalist economies the cause of the prosperity of today’s industrial nations, any more than the skin color of people from Europe was the cause of Europe’s ascendancy during its age of empire. Still, just as the unmentionable realities behind European imperialism made it inevitable that there would be attempts to justify it via bad science, the equally awkward realities behind the ascendancy of today’s industrial powers provide the push behind well-meaning attempts to package the industrial world’s institutions for export to the Third World.

The same sort of logic, on an even deeper level, governs the relationship between the nations of the modern industrial world and the foundation of those nations’ present prosperity – the Earth’s fossil fuel reserves themselves. The hard reality is that the minority of us who happened to have been born in a few powerful countries squandered half a billion years of stored photosynthesis to give ourselves a brief period of spectacular economic abundance, and by doing so, foreclosed the chance that anybody else would enjoy that same abundance in the future. Fossil fuels are not renewable resources in any time frame accessible to our species. Every barrel and ton and cubic foot of fossil fuel we use now is subtracted from the total available to our descendants; despite an orgy of handwaving, no other resource can provide anything approaching the glut of cheap abundant energy on which our lifestyles of relative privilege depend.

Yet this point of view is at least as unmentionable in polite society just now as were the gritty realities of European colonialism in its time, or the equally gritty facts underlying the ascendancy of the world’s industrial nations over the Third World today. The strenuous efforts to find a racial basis for European supremacy a century ago, and the equally vigorous efforts to hold up contemporary Western institutions as the key to prosperity and peace in the Third World today, thus have precise equivalents in the enthusiasm with which every imaginable alternative energy resource gets treated by government officials and media pundits throughout the industrial world.

None of these resources can actually provide the cheap abundant energy needed to maintain the kind of society we have today. I know that this is a controversial statement just now. Still, it’s worth noting that every alternative energy resource that’s actually been brought into production has turned out, at best, to provide a modest increment to existing energy supplies, and that only if you don’t keep track of the energy subsidy the new resource gets from fossil fuels. Of course technologies that haven’t been put into production look more promising, and the further they are from implementation, the more impressive they look; hype, often geared to the very practical goal of selling shares in IPOs, is at least as abundant in the energy field as anywhere else.

And this, dear reader, is where the gap between our society’s official respect for science and its real attitudes toward the world shows up with remarkable clarity.

Once again, the role of the B-movie heavy in this drama is played by the second law of thermodynamics, better known as the law of entropy. As mentioned in a previous post, this is the gold standard of physics, the law you can’t break without, as Sir Arthur Eddington put it, collapsing in deepest humiliation. Everybody in the industrial world with the least smattering of a scientific education knows about it, or at least was introduced to it, and yet next to nobody wants to talk about how it affects the emerging energy crisis of our time.

The crucial implication of the law of entropy, for our purposes, is that it’s not energy as such, but a difference in energy potential, that allows work to be done. Imagine two smooth round boulders of equal weight, one of them sitting on a flat plateau and the other sitting on the slope of a steep hill. If the two are at the same distance from the center of the Earth, gravitation gives them exactly the same amount of potential energy. Still, if you give the one on the plateau a push, you aren’t likely to do anything but strain your muscles, while if you give an equal push to the one on the slope, you may send it rolling down the hill, squashing everything in its path.

The difference is that every part of the plateau has the same energy potential due to gravity, while every part of the slope does not have the same potential, and the boulder rolling down the slope can cash in some of the difference in potential to keep itself moving. The greater the difference in potential, the greater the payoff in terms of energy released. Notice, though, what happens when the boulder on the slope finally lurches to a stop at the bottom of the valley below: it stops, and another push won’t get it going again. It still has a lot of potential energy in that position – it has, in theory, 4500 miles to fall until it reaches the center of the earth – but there’s nowhere it can go to release any of that energy. Without a difference in potential, how much energy you’ve got is a meaningless statistic. (This is, incidentally, why the quest for zero point energy is an exercise in absurdity; by definition, zero point energy is at the lowest possible potential state, and therefore cannot be made to do any work at all.)

The same rule applies to every energy resource: there has to be a difference in potential that allows energy to be released, and the bigger the difference, the bigger the benefit. With petroleum, the difference is in chemical energy. Those long chains of carbon and hydrogen atoms have a lot of energy to release when they come apart and combine with highly reactive oxygen instead; the short chains that form natural gas have less, and the carbon in coal has less still, though it’s still a lot by the standards of other energy sources. All the extraordinary things our species has done with fossil fuels over the last three hundred years are functions, in effect, of the difference in chemical potential energy between a barrel of oil and a cloud of smoke.

Why are these reflections as welcome in the collective conversation of our time as a slug in a fresh green salad? Because they point up the profoundly shortsighted nature of the decisions that made the world in which all of us now live. The immense potential energy locked up in fossil fuels was put there by millions of years of photosynthesis. It’s as though, to return to our metaphor, living things down through the ages rolled boulders uphill and perched them high above the valley floor. After a half billion years or so, our species came along, and figured out how to roll those boulders downhill. As long as there are still plenty of boulders in place, we can continue using them, but when the rate at which we want to send boulders rolling downhill outstrips the boulder supply, it’s a waste of breath to insist that we can get the same results by bouncing pebbles across the valley floor.

This is basically what the more enthusiastic proponents of alternative energy are saying. By the time sunlight gets to us, after traversing 93 million miles of empty space, it’s simply not that concentrated an energy source; that’s why it took the Earth’s photosynthetic organisms so many millions of years to build up the energy reserves we now squander so freely. Wind and hydroelectric power are both secondhand sunlight, the product of natural cycles driven by the sun; the same is true of every kind of biofuel, of course. Nuclear energy is the one nonsolar energy resource we’ve got, but it has severe problems and limitations of its own, not least the fact that the fossil fuel inputs needed to build, run, and decommission a nuclear reactor are so vast that there’s a real question whether nuclear power is a net energy source at all. (Of course the further a nuclear technology is from actual implementation, the better it looks, and the ones that are still vaporware look best of all.)

Does this mean alternative energy is a waste of time? Of course not. Modest as the energy outputs from alternative sources are, they’re what we’ll have to work with when the fossil fuel is gone. What it means, rather, is that the particular kind of civilization we’ve built in the last three centuries will not survive the end of cheap abundant fossil fuels. A society that is used to getting things done by rolling huge boulders down steep slopes is going to have to learn to make do on the much less lavish results of bouncing pebbles across the flat.

The problem here is that very few people want to deal with that reality. The great majority will make themselves believe in zero point energy and evil space lizards and any other absurdity you care to name, rather than gulp and take a deep breath and admit that the prosperity we’ve enjoyed for the last three centuries was bought at our grandchildren’s expense. I sometimes suspect that one of the reasons so many people like to imagine an apocalyptic end to the industrial age is that sudden extinction is easier to contemplate than the experience of slowly waking up to the full extent of our own collective stupidity.

And that, dear reader, is why entropy has become the Rodney Dangerfield of the contemporary energy debate. It may be the gold standard of physics, but in the collective conversation about our future, it don’t get no respect.

******************l

I've heard those arguments before, but I can't say I'm terribly impressed.

Entropy is the boogeyman of everyone with a science degree, but innovation has the unique quality of being the killer of boogeymen. I mean, would you have every imagined a car that runs on compressed air and gets 175 miles on a tank that costs 1 English pound of electricity to fuel up? Sure, it's a shitty little car, but I'm more than willing to wait and see what happens to it in a few generations.

How about some new solar panel tech that seems to come around every year and costs half as much?

The future is not going to look like the past, and no one pretends that it will. That being said, the rate of technical innovation right now is greater than at any time in human history.

Hell, if we could avoid a Malthusian famine by starting the Green Revolution by using fertilizers and pesticide and crop-breeding, what do you think we can we do with 21st century tech like genetic manipulation, nanotech, and new materials like carbon nanotubes?

Entropy is the boogeyman of everyone with a science degree, but innovation has the unique quality of being the killer of boogeymen. I mean, would you have every imagined a car that runs on compressed air and gets 175 miles on a tank that costs 1 English pound of electricity to fuel up? Sure, it's a shitty little car, but I'm more than willing to wait and see what happens to it in a few generations.

How about some new solar panel tech that seems to come around every year and costs half as much?

The future is not going to look like the past, and no one pretends that it will. That being said, the rate of technical innovation right now is greater than at any time in human history.

Hell, if we could avoid a Malthusian famine by starting the Green Revolution by using fertilizers and pesticide and crop-breeding, what do you think we can we do with 21st century tech like genetic manipulation, nanotech, and new materials like carbon nanotubes?

Last edited by K on Tue Sep 18, 2012 6:31 am, edited 2 times in total.

Entropy is a problem in the sense that one day the sun will explode and there is probably nothing we can do about it.

The sun outputs 380 yottawatts. That's a lot. Only 170 petawatts of that makes it to Earth. That's still a lot. By contrast, global energy consumption is only 15 terawatts.

Of course, if you're really concerned about power consumption the smart thing to do would be to build a Dyson swarm. Even when you consider how inefficient microwave power transmission is, a sufficiently large network of power collection statites located close to the sun could easily throw out enough tightly focused microwaves to flash-fry the earth and boil the oceans.

The sun outputs 380 yottawatts. That's a lot. Only 170 petawatts of that makes it to Earth. That's still a lot. By contrast, global energy consumption is only 15 terawatts.

Of course, if you're really concerned about power consumption the smart thing to do would be to build a Dyson swarm. Even when you consider how inefficient microwave power transmission is, a sufficiently large network of power collection statites located close to the sun could easily throw out enough tightly focused microwaves to flash-fry the earth and boil the oceans.

The reason Solar always stays at "almost a viable alternative" is the bit where you personally have to get your car, house and so on changed over because car manufacturers aren't going to change from oil by their own choice, and I imagine BP and friends would shoot you in the face if you forced such a change.

Basically, money makes the decisions, and money says "We're going to keep burning prehistoric dead things - the less there is, the more we can charge for it!"

Basically, money makes the decisions, and money says "We're going to keep burning prehistoric dead things - the less there is, the more we can charge for it!"

Count Arioch the 28th wrote:There is NOTHING better than lesbians. Lesbians make everything better.

- nockermensch

- Duke

- Posts: 1900

- Joined: Fri Jan 06, 2012 1:11 pm

- Location: Rio: the Janeiro

I used to think exactly like this, but then I noticed this is faith-based thinking.K wrote:I've heard those arguments before, but I can't say I'm terribly impressed.

Entropy is the boogeyman of everyone with a science degree, but innovation has the unique quality of being the killer of boogeymen. I mean, would you have every imagined a car that runs on compressed air and gets 175 miles on a tank that costs 1 English pound of electricity to fuel up? Sure, it's a shitty little car, but I'm more than willing to wait and see what happens to it in a few generations.

How about some new solar panel tech that seems to come around every year and costs half as much?

The future is not going to look like the past, and no one pretends that it will. That being said, the rate of technical innovation right now is greater than at any time in human history.

Hell, if we could avoid a Malthusian famine by starting the Green Revolution by using fertilizers and pesticide and crop-breeding, what do you think we can we do with 21st century tech like genetic manipulation, nanotech, and new materials like carbon nanotubes?

Yes, our civilization survived every predicted malthusian bottleneck so far by coming up with some new awesome tech.

Does this mean we can count on that to keep progressing faster and faster? The view that we can keep accelerating towards more and more energy use is one that I think was more awesomely put up by Tesla himself, here.

The problem with that awesome Sons of Ether ethos is that it's applied Positivism. We get to have faith in our endless capacity for creativity and innovation to keep going. If the breakthrough doesn't come, we're in for the predicted archdruids's doom.

@ @ Nockermensch

Koumei wrote:After all, in Firefox you keep tabs in your browser, but in SovietPutin's Russia, browser keeps tabs on you.

Mord wrote:Chromatic Wolves are massively under-CRed. Its "Dood to stone" spell-like is a TPK waiting to happen if you run into it before anyone in the party has Dance of Sack or Shield of Farts.

It's not faith-based thinking. It's an argument based on evidence.nockermensch wrote:I used to think exactly like this, but then I noticed this is faith-based thinking.K wrote:I've heard those arguments before, but I can't say I'm terribly impressed.

Entropy is the boogeyman of everyone with a science degree, but innovation has the unique quality of being the killer of boogeymen. I mean, would you have every imagined a car that runs on compressed air and gets 175 miles on a tank that costs 1 English pound of electricity to fuel up? Sure, it's a shitty little car, but I'm more than willing to wait and see what happens to it in a few generations.

How about some new solar panel tech that seems to come around every year and costs half as much?

The future is not going to look like the past, and no one pretends that it will. That being said, the rate of technical innovation right now is greater than at any time in human history.

Hell, if we could avoid a Malthusian famine by starting the Green Revolution by using fertilizers and pesticide and crop-breeding, what do you think we can we do with 21st century tech like genetic manipulation, nanotech, and new materials like carbon nanotubes?

Yes, our civilization survived every predicted malthusian bottleneck so far by coming up with some new awesome tech.

Does this mean we can count on that to keep progressing faster and faster? The view that we can keep accelerating towards more and more energy use is one that I think was more awesomely put up by Tesla himself, here.

The problem with that awesome Sons of Ether ethos is that it's applied Positivism. We get to have faith in our endless capacity for creativity and innovation to keep going. If the breakthrough doesn't come, we're in for the predicted archdruids's doom.

The evidence is that the human race is amazingly good at solving problems that are 50-60 years in the future. We are so good that we've never failed to do it yet.

As for Tesla, I don't think his table-napkin calculations ever took into account the ability for us to create more energy efficient tech or to render whole industries obsolete. If you are going to pretend to predict the future of energy use more than 100 years in the future, that's a critical variable.

-

Username17

- Serious Badass

- Posts: 29894

- Joined: Fri Mar 07, 2008 7:54 pm

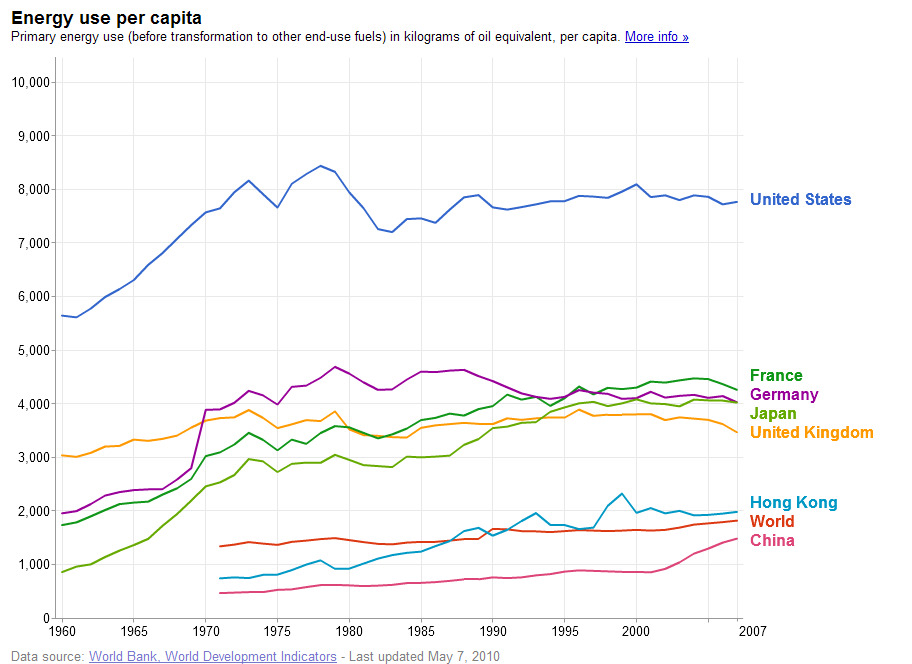

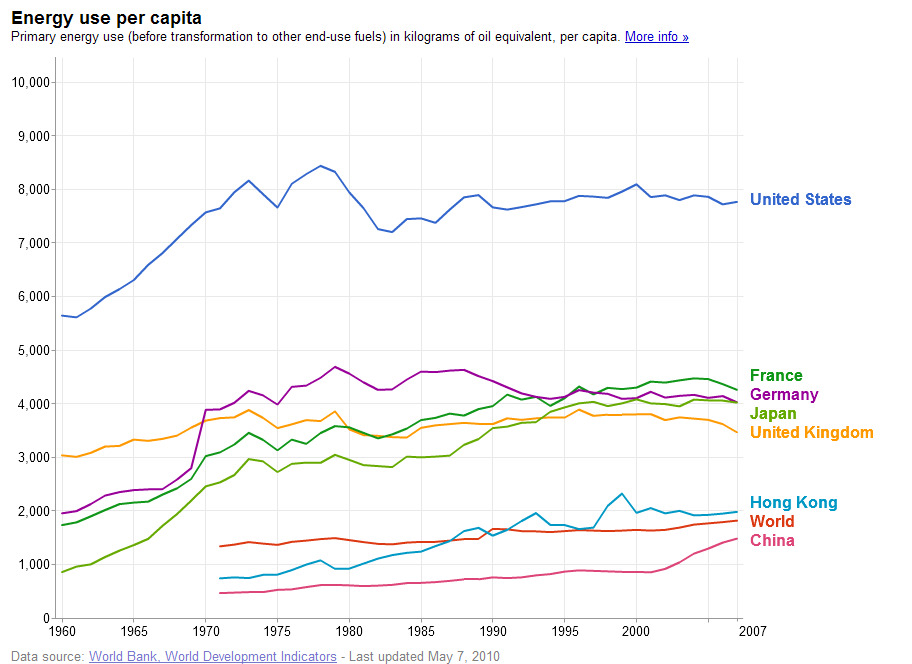

The gain of efficiency isn't religious positivism at all. It's a real and measured phenomenon:

While the average American uses more electricity and travels more distance and all that than they did thirty-five years ago, the actual oil consumed in doing so is less. The progress of technology to make more efficient use of resources is a real and quantified thing.

While the average American uses more electricity and travels more distance and all that than they did thirty-five years ago, the actual oil consumed in doing so is less. The progress of technology to make more efficient use of resources is a real and quantified thing.

Can we improve efficiency fast enough to keep from reducing quality of life? Absolutely. There's a lot of ways to increase efficiency that we've discovered that we aren't even deploying yet (high speed rail, super grids, etc.), and if things get more dire the pressure to deploy them will be greater. The problem with stagnating and dropping standards of living has much more to do with rising economic inequality than it does with running out of resources. Although running out of resources doesn't help of course.

-Username17

Can we improve efficiency fast enough to keep from reducing quality of life? Absolutely. There's a lot of ways to increase efficiency that we've discovered that we aren't even deploying yet (high speed rail, super grids, etc.), and if things get more dire the pressure to deploy them will be greater. The problem with stagnating and dropping standards of living has much more to do with rising economic inequality than it does with running out of resources. Although running out of resources doesn't help of course.

-Username17

Last edited by Username17 on Tue Sep 18, 2012 5:46 pm, edited 1 time in total.

-

Frank Shannon

- NPC

- Posts: 9

- Joined: Tue Nov 22, 2011 2:46 am

- Contact:

Why is the amount in the US so much higher than other countries like Germany / France etc?

Gary Gygax wrote:The player’s path to role-playing mastery begins with a thorough understanding of the rules of the game

Bigode wrote:I wouldn't normally make that blanket of a suggestion, but you seem to deserve it: scroll through the entire forum, read anything that looks interesting in term of design experience, then come back.

- nockermensch

- Duke

- Posts: 1900

- Joined: Fri Jan 06, 2012 1:11 pm

- Location: Rio: the Janeiro

Thread will now segue into a 4chan's "Differences between USA and Europe", thank you all for playing.ishy wrote:Why is the amount in the US so much higher than other countries like Germany / France etc?

As for the arguments for believing in our technological future, a problem I have with the "We are so good that we've never failed to do it yet." line it's that it sounds like those anthropic universe arguments: It's a given that the situation we're living right now shows a string of succeses. (Just as our life supporting planet only exists due to a string of lucky events).

The problem with "proving" that our race can keep up advancing with a greedy approach to natural resources is how do you generalize a string of successful events into a natural law. Some idiots used the fine tuned universe arguments to demonstrate that there's a god who made this universe for us. I find this proof weak. And then, yeah, how's that actually different from us pointing that mankind breaked every predicted limitation so far?

But then again, I realize this is mostly mental masturbation. One argument that could be given and defended right now for keeping up with the heavy resource use is that most (all?) proposals I read about stopping or diminishing it would make the world economies contract. And any economical contraction will mostly hurt the already poor. So, right now, it'd be downright cruel to the already existing humans to try to hold down our pace.

@ @ Nockermensch

Koumei wrote:After all, in Firefox you keep tabs in your browser, but in SovietPutin's Russia, browser keeps tabs on you.

Mord wrote:Chromatic Wolves are massively under-CRed. Its "Dood to stone" spell-like is a TPK waiting to happen if you run into it before anyone in the party has Dance of Sack or Shield of Farts.

The thing is, though, that we already have the tech to solve our energy problems. The only reason we don't make heavy use of it right now is that it simply isn't cost efficient compared to current solutions. We have the ability to do it today, but not the will, because its easier to burn fossil fuels.

Heck, we could have a permanent city on the moon right now. We don't because it costs too much. Most people aren't willing to invest large sums of money into a venture until it hits the point where they can actually make a profit off of it.

Heck, we could have a permanent city on the moon right now. We don't because it costs too much. Most people aren't willing to invest large sums of money into a venture until it hits the point where they can actually make a profit off of it.

- Josh_Kablack

- King

- Posts: 5318

- Joined: Fri Mar 07, 2008 7:54 pm

- Location: Online. duh

As a wild guess, it probably has a lot to do with the relative investments into different types of transit infrastructure, which in turn has rather a lot to due with geography and urbanization.ishy wrote:Why is the amount in the US so much higher than other countries like Germany / France etc?

The US is a vast landmass and most of our governments' transportation monies are spent subsidizing ways for privately owned automobile to get places faster and safer (with paying the TSA to frisk air travelers a distant second) and a relative pittance allocated toward urban mass transit, railways and waterways transit.

"But transportation issues are social-justice issues. The toll of bad transit policies and worse infrastructure—trains and buses that don’t run well and badly serve low-income neighborhoods, vehicular traffic that pollutes the environment and endangers the lives of cyclists and pedestrians—is borne disproportionately by black and brown communities."

US population density is crap compared to the rest of the world, so we use a lot less public transit and lot more cars. I expect that this is why we use so much energy per capital.Josh_Kablack wrote:As a wild guess, it probably has a lot to do with the relative investments into different types of transit infrastructure, which in turn has rather a lot to due with geography and urbanization.ishy wrote:Why is the amount in the US so much higher than other countries like Germany / France etc?

The US is a vast landmass and most of our governments' transportation monies are spent subsidizing ways for privately owned automobile to get places faster and safer (with paying the TSA to frisk air travelers a distant second) and a relative pittance allocated toward urban mass transit, railways and waterways transit.

Plus, our standard of living is super high. We actually heat our homes instead of putting on more clothes and cool them instead of sweating our asses off.