Today we're going to do something a little bit different. Rather than just having one person get all trashed and rant about a book, we're going to have two. AncientHistory and I are going to be reviewing the Factol's Manifesto together. I think AncientHistory is going to be on Team Nostalgia and I am going to be on Team Rage. In any case, there will be much reading, much ranting, and much drinking.

Sigil, the default setting for PLANESCAPE™ has its literary roots in Michael Moorcock’s Tanelorn, First Comics’ Cynosure, Edward Bryant’s Cinnabar, Roger Zelazny’s Amber and Roadmarks, and more interdimensional bars than I can readily name. The great thing about the City of Doors is that it deliberately tosses out a lot of the conventional nonsense that Mister Cavern and the players have to sort through—government, currency, geography—and PCs of any level can interact with a bunch of things that would normally kill them if encountered in a dungeon setting. It’s a lawless hive of interdimensional scum and villainy, and Luke Skywalker wouldn’t have gotten out of there without a tattoo and losing his virginity to a transvestite modron.

More mead for me then! PLANESCAPE™ was part of TSR's push to make settings for 2nd edition AD&D that would sell AD&D to people and also make the slightest fuckwidth of sense and hold together given the crazy shit that was canonically available for high level AD&D characters to encounter. Other endeavors in this series tended to sequester the high level bullshit far away. Ravenloft divided it all up with mists, Birthright just forbid people from getting to high level, and so on. Planescape went straight for the jugular by trying to get a handle on the multiple infinities that AD&D had running around. Kind of a tall order to make any sense of, remember that this is the map of the outer planes that they inherited:

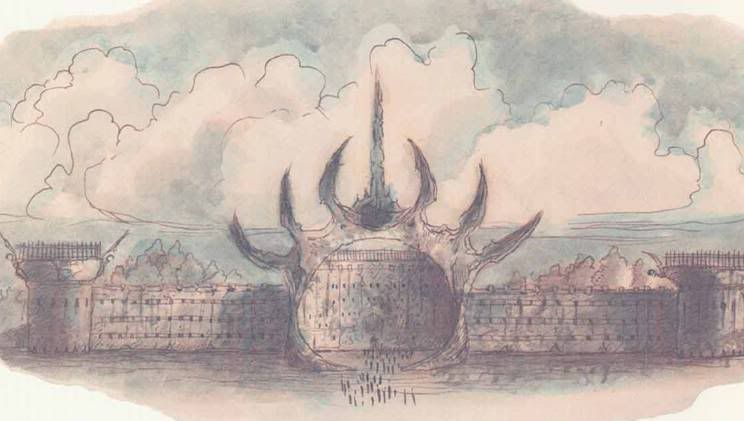

And they turned it into this:

All fixed!

Like Dark Sun, an effort was made to give PLANESCAPE its own distinctive identity by way of the artistic talents of Tony DiTerlizzi (who is now much more famous for the Spiderwick books). For reference, this is what passed for a furry back then:

On top of that, they had a custom font that eerily presaged certain elements of 133+ and a penchant for using this godawful pale brown color for headers and quotes that probably made scanners shit themselves and die. Like other AD&D books, the division between fluff and crunch was minimal, so that you could read two paragraphs of fluff and then the line you’re reading ends with telling you to go buy A Player’s Guide to the Planes for more info.

The big problem with all out war between nine different alignments is that it's basically unplayable, especially if the PCs aren't all exactly the same alignment (which there was every reason to believe they would not be). The Factions were supposed to be groups that could have goals that made any sense to people (while TSR employees were still required to claim that you could make sense out of Law and Chaos, I think most of them understood at least on some level how fucking stupid it all was), and also to be groups that were small enough that they could have meaningful successes and failures and agendas you could plausibly justify working for or against. Just have that floating in the back of your mind in the rest of the book: the Factions are there to make the philosophies and battles of ideology that define the planes more accessible to the player characters.

Credits & Introduction

A lot of familiar names here, not all of them present. If the whole book looks like a series of Dragon Magazine articles circa 1995, well, there’s a good reason for that: Rich Baker was involved. One of the fun things from this unique time period is the emergence of what TSR called the Electronic Prepress Coordinator. I’m not entirely sure what the fuck that is, but given that this isn’t RIFTS were somebody was still cutting and gluing things together into a physical document, I think that was an early precursor to what layout artists do nowadays – take the art, and the text, and put them together and make them pretty for print.

Almost everyone who worked on this book was out of the TSR writing pool by the time 3rd edition came out, so no one gives a fuck about these people. Considering how well this book was received, I find that odd. The only names you'll recognize are Rich Redman and Monte Cook who both get thankyous rather than credits per se. I suspect that they also didn't get paid any money, because we are talking about TSR in 1995. Rich Redman gets extra special thanks because he wrote a Dragon Magazine Article about faction ranks that this book is apparently going to steal from. Na zdravi!

The introduction officially begins on page 2, because the table of contents was on page 1, and it about sets the tone for the entire book both in form and content. 1995 was very big on the book as a pseudo-artifact, a literal document from another place that a reader could pick up in their hands and immerse themselves in the world, hopefully while not stroking off to any of the bare breasticles on display in the margins. Not that we’ve come across breasticles just yet. So most of the book is written as in-character, though again it suddenly veers out-of-character to plug additional AD&D PLANESCAPE books and provide game information with no fucking notice. There are little floating quotes from random people that the main text works around—unlike Shadowrun or Earthdawn, AD&D never quite figured out a non-intrusive way to add annotations. In fact, the main text has to do double-time being indented around the weird graphics snaking across the page; they look like pieces of crumpled paper with a slight 1st-generation photoshop style shadowing effect.

The whole “many Bothans died to bring us this information” opening was supposed to make you want to read the rest of the book. But really it underscores how completely ridiculous this all is. We aren't talking about infiltrating North Korea or something, we're talking about scouting out the policies of the political parties of your home town. Getting this information for each faction should be like five minutes of work for a Doppelganger. Or a Succubus. Or really any shapeshifting telepath you want to name. This is second edition AD&D, so there are a lot to choose from.

To add to what Frank said, this is a more-or-less tried-and-true formula you see in a lot of books even today—there’s an official-sounding term for it which I completely forget, but I’ll call it the Forbidden Fruit Gambit. The more secret and verboten it’s supposed to be, the more difficult and dangerous it was to get into your hands, the more readers are supposed to want it. Shadowrun used this same sort of trick many times in books like Tir Tairngire, Tir na nOg, and Aztlan; a lot of occult books still use it. However, as Frank said, for this to work the premise has to be believable and the contents have to deliver a little—but by the Nine Hells, this is Sigil. Some of these groups should be standing on the sidewalk handing out pamphlets in many languages advertising their views.

No doubt the ever present Planscape-speak is going to grate on my nerves tremendously by the time we get to the end, but for now I'm handling it all OK. I will say that it is beyond fucking bizarre to write your introduction in-character and then use the trademark symbol on the word “PLANESCAPE™”. It was the mid-nineties, and apparently no one ever told authors back then to segregate their language between when they are talking to the characters in the world and when they are talking to the players of those characters.

The index promises us a 6 page introduction, but it is in fact only 3 pages long. Each subsequent chapter is dedicated full-on to a single faction. I'm not sure if the different faction chapters were written by the same or different people because the book credits three designers but no writers at all. The intro gives us a general system for ranks in any factions, which I'm pretty sure is worse than having had them just not do that. The bottom rung are “Namers”, which is a fine enough word for people who identify as members of the party but don't have any especial pull in it. The other three are (in order) “factotum”, “factor”, and “factol”. Someone obviously thought they were being super clever by having the three ranks above new recruit all be a variation on the word “faction”. But that's super confusing. Also, “factol” is not a word but “factotum” means a personal assistant to someone high up, while “factor” just means someone who is acting on orders from someone else. Meaning that by any rational reading, their name for rank 2 is a higher ranking name than their name for rank 3. Considering how close the words are to each other, having them ranked differently than their English definitions would imply is certainly unfortunate.

Factions in Planescape remind me a lot of the gangs from The Warriors; they’re all supposed to wear the same outfit so that they seem slightly less silly, and some gangs are supposed to be more bad-assed than others but you can’t tell just by looking. The quick reference guide to Factions is mostly worthless, but I like that they at least make an effort to sum up the binding philosophies which are the only thing putting these people together in one sentence. In this way they’re a bit like the various sects, clans, and tribes from World of Darkness, but with less hard-coded mechanics (at least at low membership status).

Many of the fifteen factions make even less sense than the nine alignments do, but I guess we'll get to that when he hit the individual faction writeups. Rebutting the minimalist descriptions in the table is unfair. I will say however that the general rule that you can only be in one faction is pretty hard to defend. Sure, there's mechanical reasons for it (being in a faction gives you bonuses, being in two factions would give you two sets of bonuses), but there's no in world reason for it that makes any sense. The faction philosophies don't always address the same things, with some having extremely esoteric philosophies about the nature of perception or the meaning of gods, while others have extremely concrete philosophies about what constitutes good public policy. It's like insisting that you can't be a democrat or a republican if you've already declared yourself to be a Christian or a Buddhist... or an electrician for that matter.

Just adding to what Frank said, it also doesn’t help that there are at least a couple hundred “dead” Factions, some of which are more interesting than the ones that finally made it into this book. (Google: “Incantifier”) Likewise, there are some unfortunate misconceptions of language here—the Anarchists of Planescape are not real-world anarchists—and trying to map these philosophies to the nine-alignment planar setting is weird. Neutral Good but want to be an Anarchist? Fuck you, their headquarters are in Carceri.